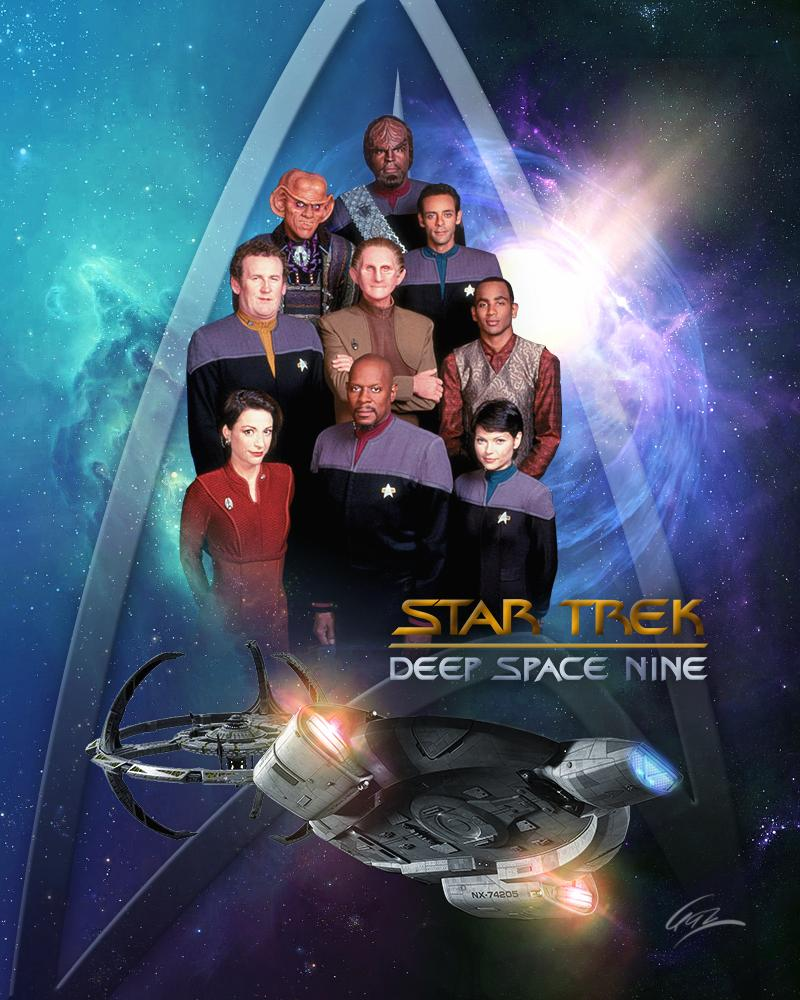

TO BOLDLY REVIEW #14 – DEEP SPACE NINE (1993 -1999)

Created by: Rick Berman, Michael Piller

Based on Star Trek: by Gene Roddenberry

Showrunners: Michael Piller (1993–1995) and Ira Steven Behr (1995–1999)

Main Cast: Avery Brooks, René Auberjonois, Terry Farrell, Cirroc Lofton, Colm Meaney, Armin Shimerman, Alexander Siddig, Nana Visitor, Michael Dorn, Nicole de Boer, etc.

Theme music composer: Dennis McCarthy

*** MAY CONTAIN SPOILERS ***

It’s been over a year since I reviewed the Star Trek feature films here. Thus, much of 2022 was spent watching the seven series of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. The fact that I got through all seven seasons of the show illustrates two things:

- I am determined to finish this viewing project of watching every Star Trek produced film and television show released from the original series to now!

- Star Trek: Deep Space Nine was a really excellent show that made me want to watch it the end.

While containing lots of genre and narrative similarities to the previous Trek television productions, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (DS9), expanded further the characters, worlds and vision established brilliantly by The Next Generation. Crossing over and surpassing the TNG timeline, DS9‘s narratives centralized around the space station positioned close to the planet of Bajor.

The Bajorans occupy the Alpha Quadrant and had one of the oldest and richest cultures in Star Trek lore. Driven by a spirituality similar to Buddhism, they are a proud people who suffered greatly during the invasion by the Cardassians, who built Deep Space 9 to control the Bajorans and the Alpha Quadrant. After the defeat of the Cardassians, Starfleet were assigned to manage DS9 and the series starts with Captain Benjamin Sisko (Avery Brooks) taking his place as commander of the station. To his surprise, Sisko becomes “Emissary” to the Bajoran prophets. A holy position which drives many storylines throughout the series and conflicts with the logical aspects of his role as Captain.

Deep Space Nine has many fine standalone episodes, however, what makes it differ greatly from the previous franchise series is the complex narrative and character arcs which dominated the latter seasons. These were directly linked by the brutal war which developed between Starfleet, their allies and the Dominion and the Cardassians. Personally, I could have done without many of the romantic “pairings-off” we got between the characters, however, they did raise the emotional stakes for them and brought greater narrative resonance. Lastly, the expansion of the Star Trek universe through use of the wormhole, allowed many other alien species to be introduced to the ever-growing Star Trek universe.

While sci-fi shows can live and die on their scientific concepts and themes, great characters are always at the heart of Star Trek. Sisko is a commanding presence throughout, yet Odo (René Auberjonois), a shapeshifter, was arguably the most complex of all characters, especially when a massive narrative reveal is dropped during Season 3. The familiar face of Worf (Michael Dorn) joined in Season 4 and he provided seriousness when compared to the more energetic characters of Jadzia Dax (Terry Farrell) and the scheming, but humorous Ferengi, Quark (Armin Shimerman). The Bajorans on the station were represented by Nana Visitor’s formidable, Kira Nerys, while Doctor Julian Bashir (Alexander Siddig) and Miles O’Brien (Colm Meaney) had a fine bromance. Finally, Deep Space Nine also had some fantastic guest actors, notably Louise Fletcher, Frank Langella, Iggy Pop, Tony Todd, James Darren and Andrew Robinson as Garak. The latter two actors became virtual regulars and Garak, the mysterious and exiled Cardassian, was probably my favourite character in the whole show.

To end this short review I’d like to pick seven of my favourite episodes – one from each season. They represent some of the best examples of, Deep Space Nine, an often brilliantly written, powerfully acted, funny and moving science fiction series.

DEEP SPACE NINE – SEVEN GREAT EPISODES

1. EMISSARY – EPISODE 1

A fine introduction to the characters, setting and themes which will dominate the next seven seasons.

2. THE JEM HADAR – EPISODE 26

A brilliant episode which introduced the fearsome Dominion soldiers, The Jem Hadar.

3. IMPROBABLE CAUSE / THE DIE IS CAST – EPISODES 20 & 21

Odo investigates a murder attempt on Garak on the space station. Their complex relationship thickens within a superbly scripted espionage thriller, full of twists and revelations.

4. THE VISITOR – EPISODE 3

An amazingly involving narrative which finds Sisko lost in a temporal void, with his son, Jake, prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice to save his father.

5. TRIALS AND TRIBBLE-ATIONS – EPISODE 6

An incredible episode full of amazing production values as it merges both present and past characters from Star Trek. The DS9 crew are sent back in time where they encounter their Enterprise predecessors and those damned pesky Tribbles.

6. FAR BEYOND THE STARS – EPISODE 13

Developed like a BBC Play for Today drama, this episode is thematically meta-rich, exploring science-fiction writing and racism in 1950’s America. How Avery Brook’s dual identities of Benny Russell and Captain Sisko connect across the universe is enigmatic, poetic and utterly compelling.

7. WHAT YOU LEAVE BEHIND (Parts 1 and 2) – EPISODEs 25/26

Despite replacing Jadzia with an inferior (Ezri) Dax, and containing a few unnecessary filler episodes with that character, the final season ultimately brought the war with the Dominion to an astounding dramatic conclusion. Sisko’s journey as the Emissary also reached a spiritually emotional and intelligent denouement. One of the best final television seasons of all time, perhaps?

![[BOOK REVIEW] A Sense of Dread: Getting Under the Skin of Horror Screenwriting by Neil Marshall Stevens](https://thecinemafix.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/100-best-horror-films-of-all-time-featured-10-panels-min.jpg?w=672&h=372&crop=1)