CINEMA REVIEW: THE BRUTALIST (2024)

Directed by Brady Corbet

Written by: Brady Corbet & Mona Fastvold

Produced by Trevor Matthews, Nick Gordon, Brian Young, Andrew Morrison, Andrew Lauren, D.J. Gugenheim and Brady Corbet.

Cast: Adrien Brody, Felicity Jones, Guy Pearce, Joe Alwyn, Raffey Cassidy, Stacy Martin, Emma Laird, Isaach de Bankolé and Alessandro Nivola.

Cinematography Lol Crawley

Edited by Dávid Jancsó

*** MAY CONTAIN SPOILERS ***

A new wave of American filmmakers—directors like Todd Field, Robert Eggers, and Brady Corbet—have emerged as some of the most technically proficient and ambitious voices in contemporary cinema. Their work is marked by rigorous formal control, deep thematic ambition, and an almost obsessive dedication to craft. These filmmakers, arguably influenced by auteurs like Sofia Coppola and Paul Thomas Anderson, demonstrate an understanding of film language that is both deeply referential and boldly experimental. Whether it’s Eggers’ meticulous historical recreations, Field’s austere and cerebral storytelling, or Corbet’s overtly intellectualized narratives, they all exhibit an undeniable mastery of their medium. Their films, often dense with literary and philosophical allusions, cater to cinephiles who relish formal precision and narrative audacity.

Yet, for all their brilliance, there’s an argument to be made that their work veers into self-indulgence, if not outright pretension. Their films sometimes feel like exercises in artistic superiority, catering to an audience that appreciates the challenge but perhaps not the emotional accessibility that cinema can offer at its best. Whether it’s the cold remove of TÁR (2022), the self-serious mythologizing of The Lighthouse (2019), or the arch, affect-laden approach of Vox Lux (2018), these works often feel encased in a layer of knowing detachment. There’s a fine line between intellectual rigor and a kind of smug, insular artistry, and some critics argue that these filmmakers, however talented, sometimes tip too far in the latter direction—prioritizing aesthetic and conceptual ambition over genuine human connection. I mean, I love a lot of these filmmakers’ work, but I was raised on the American films of Coppola, Scorsese, DePalma, Spielberg, Lucas and Friedkin; auteurs who knew their art, but also how to entertain the audience too.

In Corbet’s, and film partner’s Mona Fastvold’s, phenomenally designed and constructed film, The Brutalist (2024), Adrien Brody portrays fictional László Tóth, a Hungarian-Jewish architect and Holocaust survivor. Brody’s is an incredibly memorable piece of work, acting as a spiritual performance sequel to his Oscar-winning role in The Pianist (2002). But rather than focus on an individual attempting to escape the Nazis during the war, the narrative concentrates on Tóth, who arrives in post-war America with nothing but his talent and ambition, only to find himself trapped in a system that celebrates his work while rejecting him as a person. In America, racism is delivered with a smile, and generosity is a means of control. High society rewards Tóth but also suffocates him with subtle condescension, as he is paraded around as an artistic trophy but never fully embraced as an equal.

As an epic character study of the life of an immigrant and exploitation of the financially stricken Jew in America, The Brutalist (2024), is a powerful work. Such themes compel us to think of today and the fact that America continues to struggle with the integration of people travelling there, even though it was built with the hands of migrant families. Here the screenplay exerts true power in critiquing the United States’ treatment of those travelling to America with hope. As the narrative unfolds across the decades, Corbet, Fastfold and Brody illustrate the slow erosion of Laslo’s dreams in an America that welcomes his work but not his humanity. As the key antagonist, Harrison Lee Van Buren, Guy Pearce delivers another chilling and precise character study. Van Buren is a spoilt, rich and brattish man whose charm and refinement mask a deeply exploitative nature.

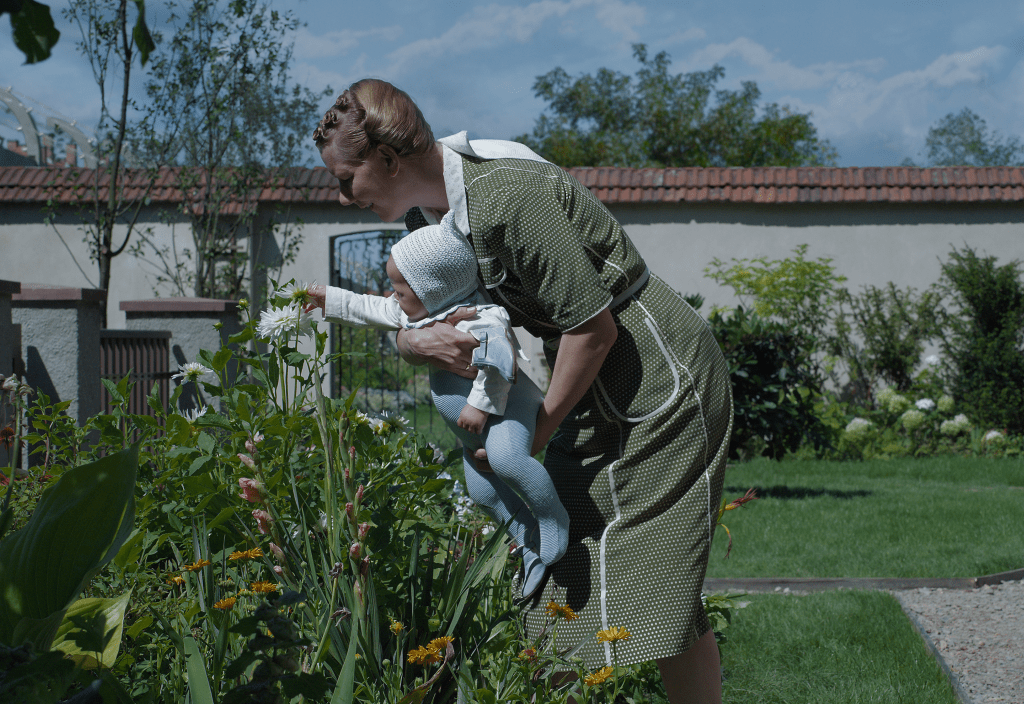

Photographically, The Brutalist (2024) is indeed a work of art. Lol Crawley and the production team immerse viewers in a stark, architectural visual language—monolithic structures, rigid compositions, and a muted, desaturated color palette mirroring the emotional and physical isolation Tóth experiences. Yet, for for all its incredible craftsmanship and bold cinematic ambition, the film is a test of endurance—an unrelenting, patience-draining experience that stretches well beyond three hours. Even the inclusion of chapters, and a self-consciously “prestigious” intermission only serve to amplify the film’s pretensions, prolonging the agony of watching layer upon layer of misery unfold like a slow-moving roller-coaster that induces motion sickness with no escape. It’s a brilliant film that demands submission rather than engagement, wielding its bleakness like a weapon against the audience’s stamina. It will probably win the Academy Award for Best Film. That or Wicked (2024).