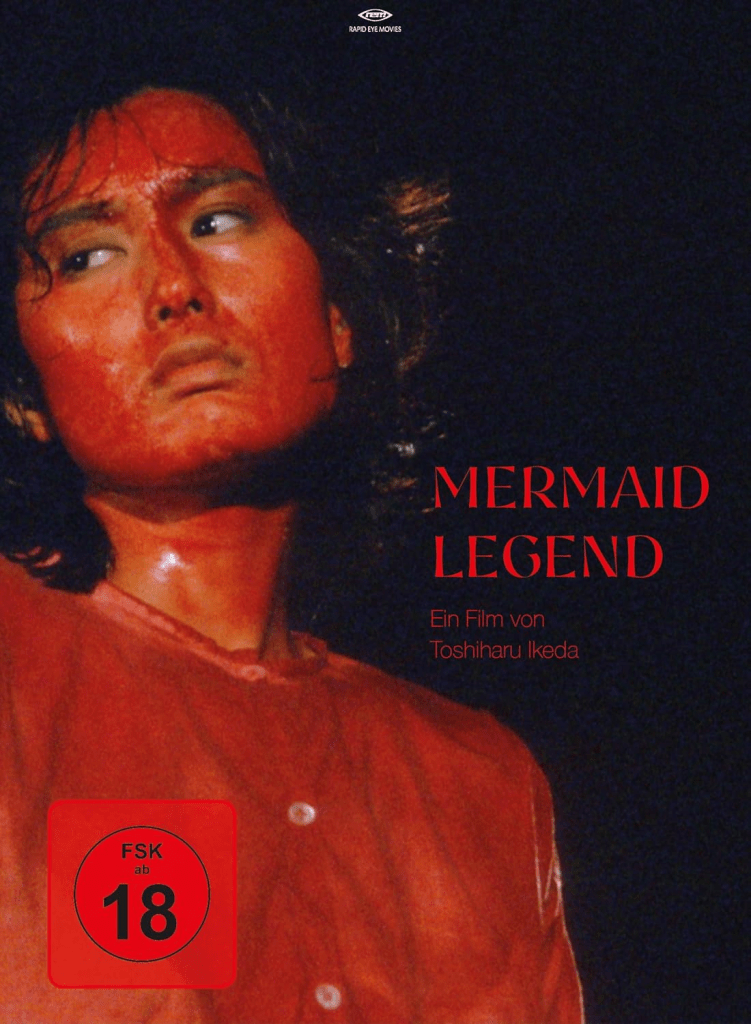

Cult Film Review: Mermaid Legend (1984)

Directed by Toshiharu Ikeda

Screenplay by Takuya Nishioka

Main cast: Mari Shirato, Junko Miyashita, Kentarō Shimizu, Jun Etō, etc.

Cinematography by Yonezou Maeda

Music by Toshiyuki Honda

*** MAY CONTAIN SPOILERS ***

I took a gamble on an unknown Japanese film at the Nickel Cinema and walked out genuinely shaken. Mermaid Legend (1984) isn’t just a cult oddity—it’s a film that mutates before your eyes, seducing you with beauty before drowning you in blood. I was stunned by how something so lyrical could also be so brutally confrontational.

The story begins almost modestly, as a coastal drama about a fisherman and his wife, Migiwa. They bicker constantly, their marriage worn thin by poverty and exhaustion, yet there’s an undeniable bond beneath the arguments. That fragile domesticity is shattered when the fisherman stands in the way of an industrial development scheme. The business developers—faceless, polite, and utterly ruthless—have him murdered, disposing of his life as casually as industrial waste.

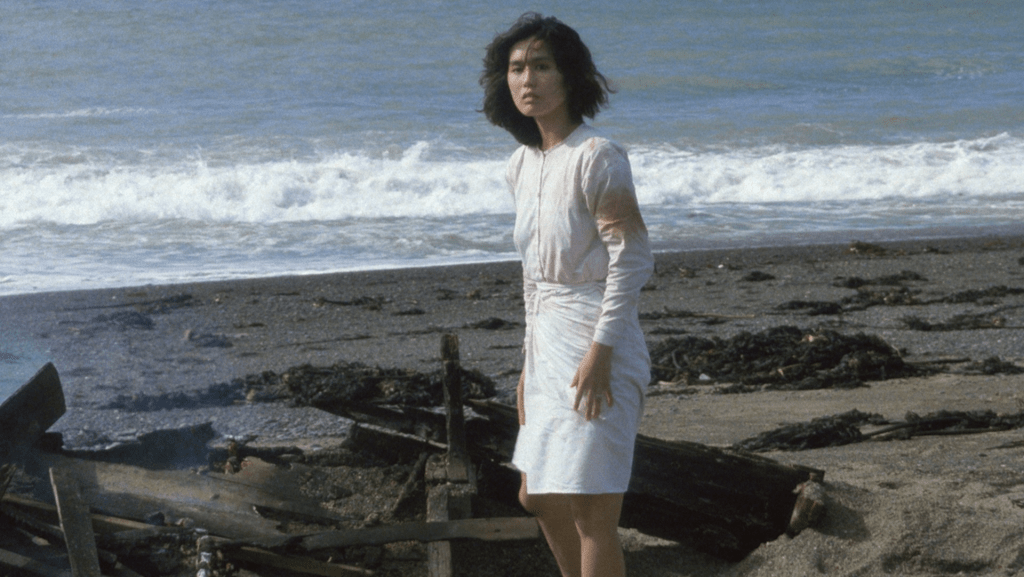

From there, Mermaid Legend (1984) transforms again. What starts as marital realism becomes a corporate espionage murder mystery, steeped in anger at nuclear energy, environmental destruction, and the cold machinery of corporate greed. Migiwa, a powerful-lunged pearl diver, initially hides, retreating into grief and the sea itself. But this is not a film about quiet mourning. When she decides to act, she does so with mythic force.

Played by the ethereal and astonishing Mari Shirato, Migiwa becomes something halfway between woman, avenging angel, and sea spirit. Shirato’s performance is magnetic—serene, sensual, and terrifying. As her vengeful pursuit begins, the film plunges headlong into extreme violence and explicit sexuality, reclassifying itself yet again as one of the most shocking exploitation epics I’ve seen from Japan in recent years. These scenes aren’t gratuitous in the lazy sense; they’re confrontational, weaponized, daring you to look away while refusing to let you feel comfortable for a second.

What makes Mermaid Legend (1984) so intoxicating is how its elements collide. Poetic underwater cinematography turns the ocean into a womb, a grave, and a cathedral. Religious, angelic, and environmental imagery blur together, as if Migiwa is both martyr and executioner. The music is heavenly—soaring, mournful, almost sacred—creating a surreal contrast with the carnage on screen. Beauty and brutality coexist in the same frame, each intensifying the other.

And then there’s the ending. The final, elongated pier stabbing rampage is completely off the chart—relentless, bloody, and hypnotic. It plays out like a ritual rather than an action sequence, stretching time until violence becomes abstraction, then meaning, then release. By the time the last body falls, Mermaid Legend (1984) has fully shed realism and entered the realm of legend, justifying its title in blood.

This is a film that shouldn’t work, yet does—furiously, defiantly. A genre-shifting fever dream that moves from domestic drama to political thriller to erotic exploitation to mythic revenge tragedy, Mermaid Legend (1984) is both beautiful and brutal, and I can’t stop thinking about it. Seeing it by chance at the Nickel Cinema felt like discovering a secret too powerful to stay hidden.