Classic Movie Scenes #16- They Live (1988) – the really long fight scene!

Directed by John Carpenter

Screenplay by John Carpenter

Based on: “Eight O’Clock in the Morning” by Ray Nelson

Produced by Larry Franco

Main cast: Roddy Piper, Keith David, Meg Foster, etc.

Cinematography by Gary B. Kibbe

Music by John Carpenter & Alan Howarth

** CONTAINS SPOILERS **

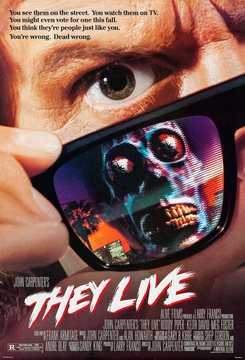

They Live (1988) is the kind of action sci-fi film that only John Carpenter could turn into a cult classic. On paper, it’s gloriously bizarre: a nameless drifter called Nada—Spanish for nothing—wanders into Los Angeles looking for work and instead stumbles into a hidden alien occupation. The key to the whole rotten system? A pair of hacked sunglasses that reveal the truth behind billboards, TV, and smiling authority figures. OBEY. CONSUME. CONFORM. No metaphor required.

Nada is played by professional wrestler Roddy Piper, whose performance is all flint-eyed suspicion and working-class fury. He’s not a chosen one or a scientist or a cop—he’s a guy at the bottom of the ladder who starts noticing the ladder itself is rigged. When Nada puts on the glasses, the world drains of colour and illusion, revealing a bleak black-and-white nightmare of propaganda and skull-faced elites hiding in plain sight. It’s one of Carpenter’s smartest tricks: truth isn’t glamorous, it’s ugly and exhausting.

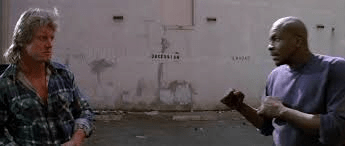

The film’s low budget sometimes shows—rubber masks, stripped-down sets, and a finale that feels like Carpenter had to sprint to the finish line before the money ran out. But that rawness is also part of They Live’s (1988) charm. It plays like a B-movie manifesto, a midnight scream against a world quietly selling your soul back to you at retail prices. And yes, the legendary alleyway fistfight is absurdly long, but it also feels like the point: waking someone up hurts, takes effort, and nobody thanks you for it.

Carpenter has been clear that They Live (1988) is a critique of consumerism, Reagan-era greed, and the way capitalism anesthetizes resistance. But watching it today, the film has mutated—like all good cult cinema—into something more unstable and more dangerous. In the age of culture wars, algorithmic outrage, and weaponized paranoia, They Live (1988) can be read in a dozen conflicting ways. Is it anti-corporate? Anti-elite? A warning about media manipulation? A Rorschach test for conspiracy culture itself? That ambiguity is why it endures.

They Live (1988) doesn’t tell you what to think—it hands you the glasses and dares you to look. And once you do, it’s hard not to feel a little like Nada: broke, angry, awake, and deeply suspicious of anyone telling you everything is just fine. As someone who has recently been researching a lot about conspiracy theories or apparent truther activists, I have my feet dangling above the rabbit hole while simultaneously holding a red pill in my hand. Yet, I am hesitant to jump in. How do I know the so-called “truthers” are not lying or serving their own agenda or career too? Which is why the fight scene is so good. Because, it shows the struggle one can have as to what to believe and who to trust. In this case, Nada is telling the truth and he is prepared to fight to reveal it.

According to IMDb “the big fight sequence was designed, rehearsed and choreographed in the back-yard of director John Carpenter’s production office. The fight between Nada (Roddy Piper) and Frank (Keith David) was only supposed to last twenty seconds, but Piper and David decided to fight it out for real, only faking the hits to the face and groin. They rehearsed the fight for three weeks. Carpenter was so impressed he kept the scene intact, which runs five minutes, twenty seconds. David recounted the event, smiling giddily as he said, “It was good fun! I never felt safer in any fight,” as Piper, a professional wrestler, coached David on how to sell the look of the punches and savage moves in exaggerated form, making it appear more brutal than it actually was.”