CINEMA REVIEW: GLADIATOR II (2024)

Directed by Ridley Scott

Screenplay by David Scarpa

Story by Peter Craig, David Scarpa

Based on Characters by David Franzoni

Produced by Ridley Scott, Michael Pruss, Douglas Wick, Lucy Fisher, Walter F. Parkes, Laurie MacDonald and David Franzoni.

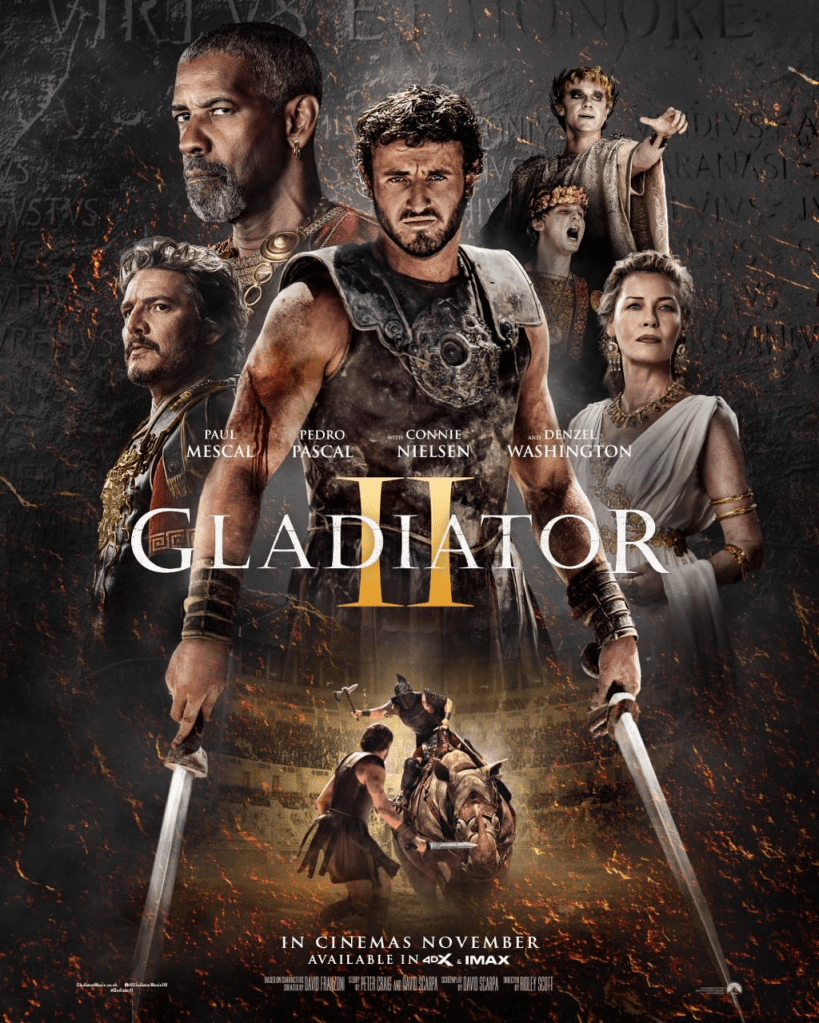

Main cast: Paul Mescal, Pedro Pascal, Joseph Quinn, Fred Hechinger, Lior Raz, Derek Jacobi, Connie Nielsen and Denzel Washington.

Cinematography by John Mathieson

*** MAY CONTAIN SPOILERS ***

Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000) stands as a modern genre classic, redefining the historical epic with its visceral storytelling, evocative visual style, and emotional depth. The film not only revitalized interest in the sword-and-sandal genre but also solidified Russell Crowe as a major star, earning him an Academy Award for Best Actor. Crowe’s portrayal of Maximus Decimus Meridius—a betrayed Roman general seeking justice—exudes both raw power and profound vulnerability, making him an enduring figure in cinematic history.

Gladiator’s superb screenplay intricately followed the structure of Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, charting Maximus’ transformation from a celebrated general to a fallen slave, and ultimately to a venerated martyr. Also invoking the archetype of one of Christopher Booker’s seven basic plots, ‘Overcoming the Monster’. Indeed, Maximus’ journey aligns with the ‘Overcoming the Monster’ archetype, where the hero confronts a seemingly insurmountable evil. Commodus and the Roman Empire embodies the “monster,” wielding unchecked power, moral corruption, and cruelty. Maximus battles not only physical opponents in the gladiatorial arena but also the corrupt system that Commodus represents. His ultimate triumph over Commodus is both personal vengeance and symbolic justice, restoring balance to a fractured world.

Finding Ridley Scott at arguably the height of his directorial power, Gladiator’s success rested on its ability to blend archetypal storytelling with deeply human emotions. It revitalized the historical epic for modern audiences by prioritizing character-driven drama over spectacle, though its battle sequences remain iconic. With its sweeping Hans Zimmer score and Russell Crowe’s unforgettable performance, the film transcended its genre, made a lot of money and become a modern myth that continues to resonate with audiences worldwide. So, the burning question is why did it take so to make a sequel?

I’d say the answer to this question is that because the original was so iconic and powerful it didn’t need a sequel. Still, when has that ever stopped the money-making behemoth of the Hollywood machine from not following up. The surprise is that it took twenty-four years to bring to the screen. Which is a similar length of time after the first one that Gladiator II (2024) is set, namely 211AD. Similarities do not cease there.

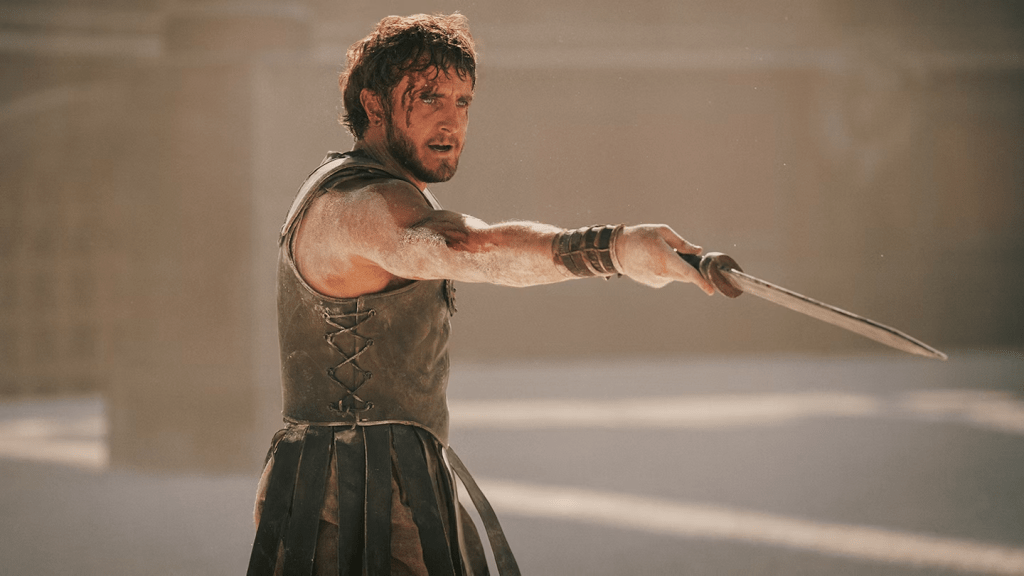

So, I will just say I had so much fun watching Gladiator II. It is an exhilarating return to the grandeur of the Roman Empire, delivering breathtaking visuals, high-stakes action, and a muscular lead performance from Paul Mescal as Hanno, a fighter with a mysterious history. However, despite its ambitious scale and technical brilliance, the sequel draws heavy parallels to the original, feeling more like a reimagining than a bold continuation. Hanno’s journey echoes Maximus’ so closely that it lacks the freshness that made the 2000 film a groundbreaking modern epic.

Indeed, Hanno’s arc is essentially a mirror image of Maximus’ but while Gladiator II adheres to the same Hero’s Journey structure that defined the first film, the beats feel overly familiar. Hanno’s transformation, while compelling, doesn’t quite reach the mythic resonance of Maximus’ odyssey. Where Maximus was a reluctant hero drawn into a larger-than-life struggle, Hanno’s motivations and journey feel more cloudy and contrived, lacking the gravitas of the original’s moral and emotional complexity. Script and character inconsistencies do not help, with Hanno too quickly switching emotions where Connie Nielsen’s Lucilla is concerned.

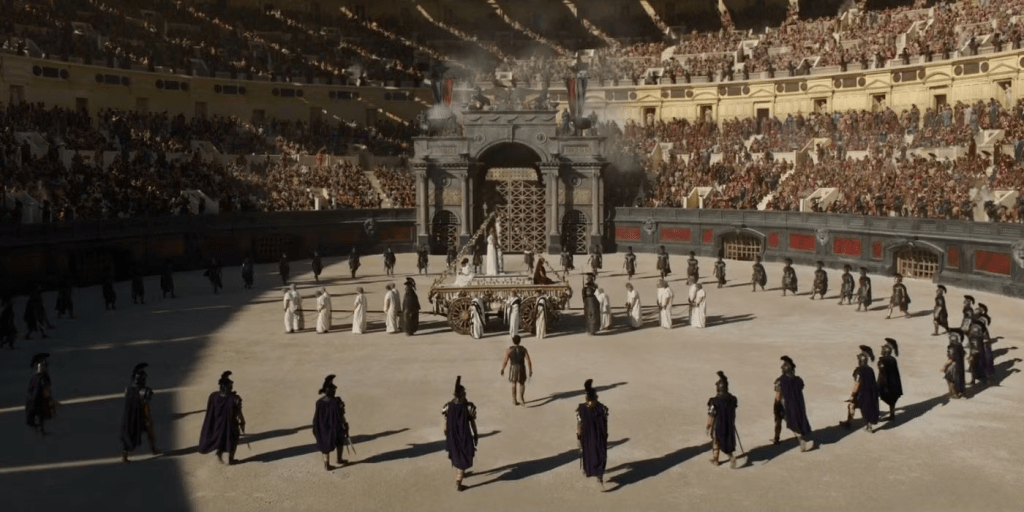

That said, the sequel contains many strengths. The world-building is as immersive as ever, with Ridley Scott’s regal direction ensuring that every frame pulsates with life and detail. The sheer energy and brutality of the Colosseum set-pieces are worth the admission alone. The flooding of the arena battle and introduction of a number of fantastic and vicious beasts are especially memorable. The action is bloody and gripping, the score soars, and the themes of resilience and justice remain timeless. Moreover, Mescal delivers a commanding performance, injecting moments of raw intensity and vulnerability into the role.

Having said that, it is Denzel Washington’s Macrinus who pulls narrative focus and power throughout. Washington brings his trademark gravitas and charisma to the role, crafting a character arc that is both morally complex and emotionally resonant. Macrinus’ journey of manipulation, becomes the film’s most compelling thread, overshadowing Hanno’s more conventional hero’s path. Washington imbues Macrinus with subtlety, allowing audiences to see flashes of vulnerability and moral conflict beneath his stoic exterior. He oscillates effortlessly between commanding authority and quiet introspection, making every line delivery impact. Washington’s natural charisma ensures that Macrinus commands attention in every scene. His dialogue crackles with intensity, and his moments of silence speak volumes, often eclipsing Hanno’s more straightforward emotional beats.

Gladiator II undeniably thrills as a cinematic experience, but its adherence to the original’s blueprint leaves it struggling to step out of Maximus’ shadow. While it showcases the enduring power of its core narrative themes, it ultimately feels more like a polished homage than a groundbreaking sequel, relying on echoes of past triumphs rather than forging an entirely new path. For fans of the original, this familiarity is a strength and weakness, yet nonetheless Scott’s epic facsimile remains a powerful and bone-crunching adrenaline rush.