Cinema Review: Bugonia (2025)

Directed by Yorgos Lanthimos

Screenplay by Will Tracy – Based on Save the Green Planet! (2003) by Jang Joon-hwan

Produced by Ed Guiney, Andrew Lowe, Yorgos Lanthimos, Emma Stone, Ari Aster, Lars Knudsen, Miky Lee, Jerry Kyoungboum Ko

Main Cast: Emma Stone, Jesse Plemons, Aidan Delbis, Stavros Halkias, Alicia Silverstone, etc.

Cinematography by Robbie Ryan

*** MAY CONTAIN SPOILERS ***

Yorgos Lanthimos has once again sneaked out of his uncanny terrarium and unleashed another piece of beautifully deranged cinema. Bugonia (2025)—a remake of Jang Joon-hwan’s cult classic Save the Green Planet!—is part sci-fi fever dream, part hostage farce, and part spiritual meltdown. It’s like Ruthless People (1986) got trapped in a socio-political, beekeeping suit and force-fed ayahuasca.

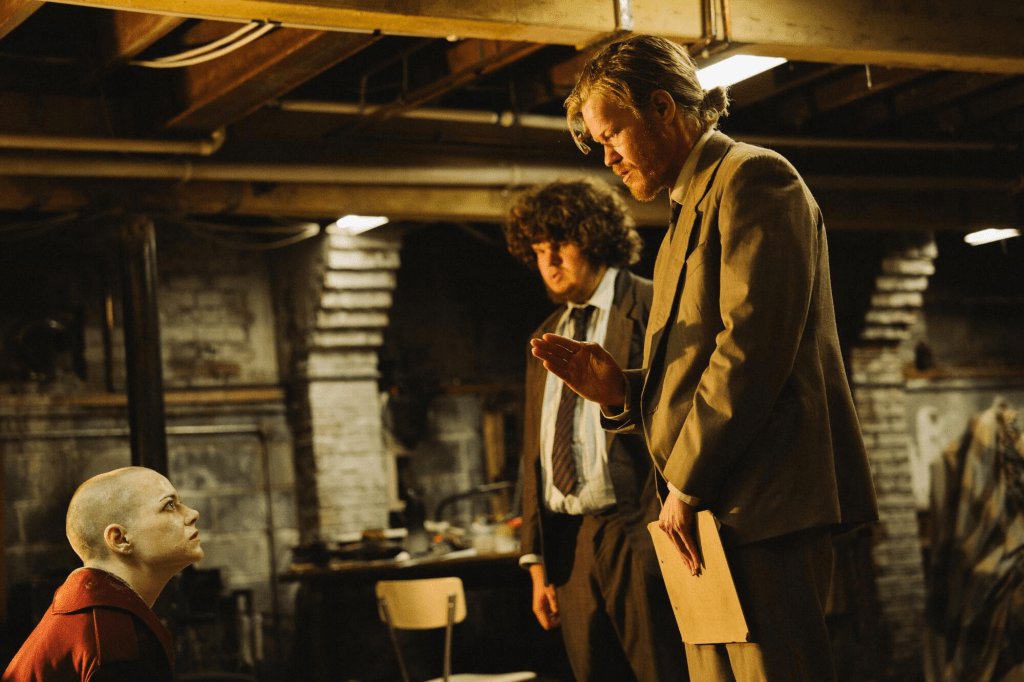

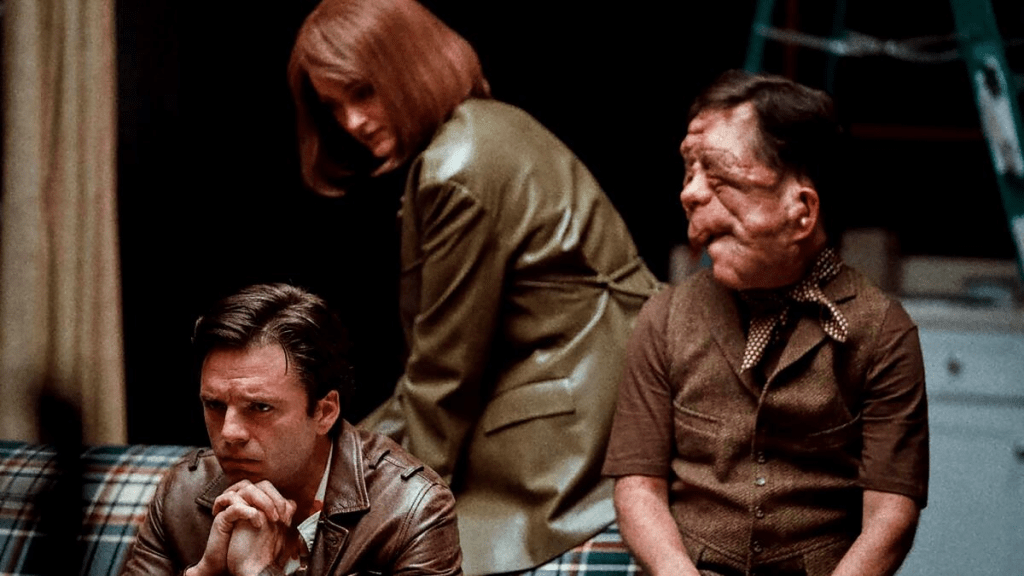

Will Tracy’s script hums with the manic energy of someone who’s read too many conspiracy subreddits and decided to turn it into Oscar bait. The film pairs Jesse Plemons (whose face seems genetically engineered for moral unease) with Alden Delbis (playing his twitchy, Kool-Aid-eyed partner in cosmic delusion) as two eco-anarchist truthers who kidnap a pharma/tech CEO, played with imperial chill by Emma Stone. Their reasoning? Well, just wait and see. It is incredibly crazy with some severe plot turns. Yet, somehow Lanthimos and his terrific cast maintain verisimilitude within the setting and just about hang onto emotional connection for the characters.

What follows is a deranged pas de trois of torture, empathy, and total philosophical collapse. Plemons and Delbis interrogate Stone with the intensity of people who’ve seen too many YouTube conspiracy documentaries, while Lanthimos and cinematographer, Robbie Ryan shoot it with the intensity of a nature documentary directed by Lucifer. There are bees. There is honey. There are monologues about pollution, pharmaceutical company threat and environmental collapse. Further, Stone, who has now fully ascended into Lanthimos’ personal pantheon of holy weirdness, plays her role like a woman being both worshipped and flayed at the same time. She’s terrifyingly serene—like she’s founded a doomsday cult and smiled through the apocalypse.

It’s all utterly ridiculous, but Bugonia (2025) thrives in that space between laughter and dread. Lanthimos once again proves that absurdism isn’t about nonsense—it’s that nonsense is the only sane response to the modern world. I enjoyed this film way more than the obtuse Kinds of Kindness (2024). It has more akin, although not as devastatingly memorable, as his earlier Greek-language classics or The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017). Moreover, if The Favourite (2018) was about power, and Poor Things (2024) was about rebirth, Bugonia (2025) is bleak, fatalistic morality tale about environmental apocalypse.

By the time the film’s final shots roll I was equal parts horrified, moved, and deeply amused. It’s an eco-horror-comedy that gorily plays like Saw (2004) meets famous beekeeping philosopher, Aristotle. Overall, Bugonia (2025) proves once again that Yorgos Lanthimos is cinema’s reigning apiarist of absurdity—and his audience are all his buzzing little drones.