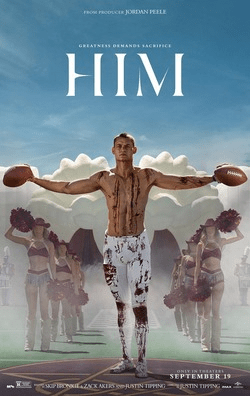

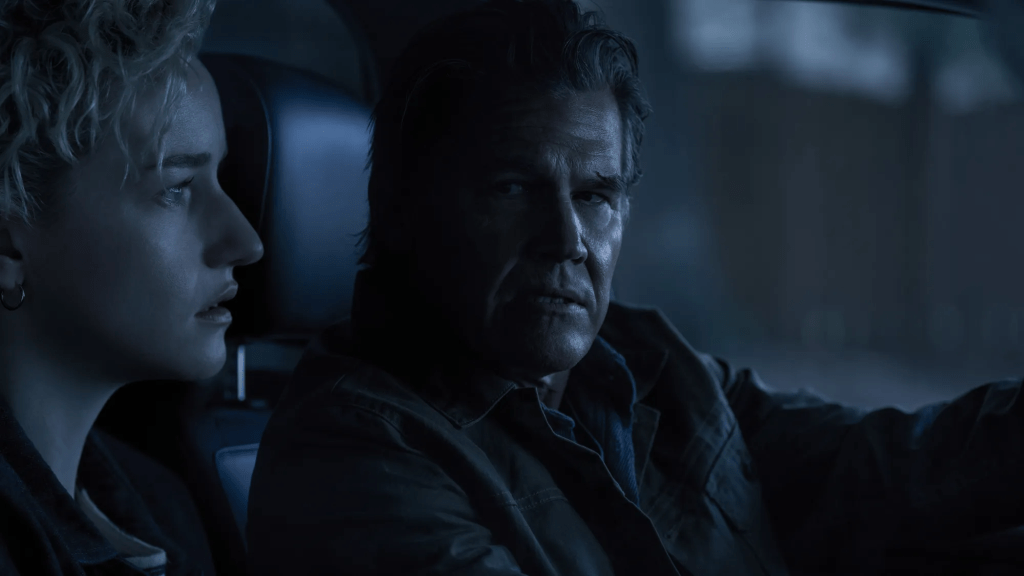

Cinema Review: Him (2025)

Directed by Justin Tipping

Written by Skip Bronkie, Zack Akers & Justin Tipping

Produced by Jordan Peele, Win Rosenfeld, Ian Cooper & Jamal Watson

Main cast: Marlon Wayans, Tyriq Withers, Julia Fox, Tim Heidecker, Jim Jeffries, Maurice Greene etc.

Cinematography by Kira Kelly

** MAY CONTAIN SPOILERS **

“In modern slang, “Him” is used to signify a person who is considered a standout or a “star” in their field, often in sports or entertainment.” — Google search result.

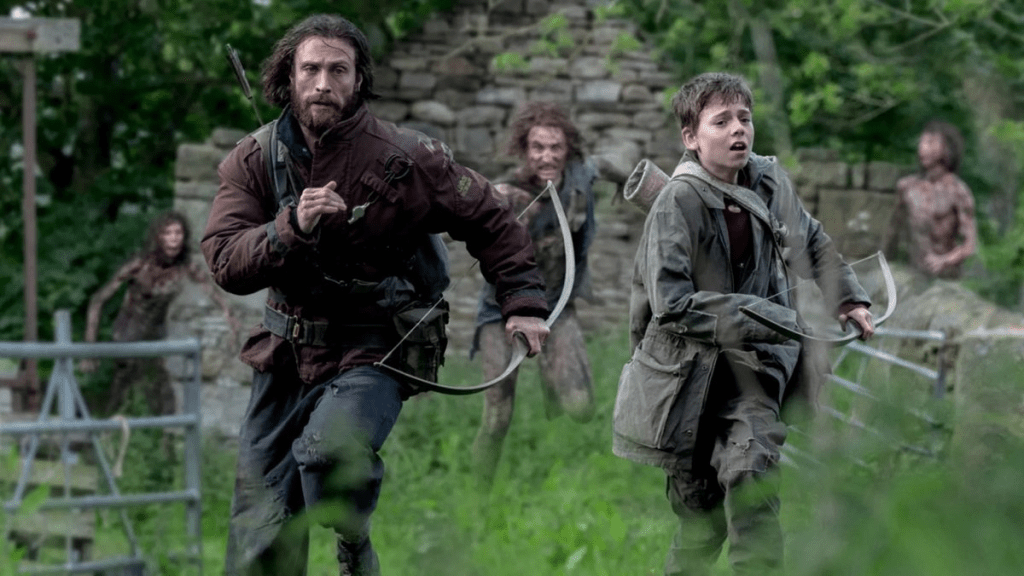

Him (2025) is a visually arresting and thematically potent descent into the underbelly of American athletic obsession — a pitch-black thriller that trades stadium lights for the strobe of psychological torment. Centered on Cameron “Cam” Cade, a young quarterback hungry to dethrone San Antonio Saviors’ reigning legend Isaiah White (a commanding Marlon Wayans), the film begins as a standard sports drama and swiftly morphs into something far darker. Director Justin Tipping captures the suffocating intensity of modern competition with a painter’s eye — sweat, blood, and neon collide in every frame, turning locker rooms and training fields into cathedrals of self-destruction.

As Cam endures Isaiah’s brutal “boot camp,” the film exposes the rot beneath the rhetoric of greatness. Fear, humiliation, and violence dominate the regimen, transforming mentorship into a form of ritualized hazing. Themes of steroid abuse, distorted masculinity, and father-son guilt weave through the story like poison veins. The omnipresence of social media — the constant surveillance, the demand for curated perfection — amplifies the claustrophobia. In its best moments, Him (2025) feels like a nightmarish hallucination of ambition, where performance and identity blur until nothing human remains.

Yet for all its kinetic power and aesthetic daring, Him (2025) stumbles when it comes to coherence. The screenplay rushes through emotional beats, failing to give its characters space to breathe or evolve. Key relationships and motivations are truncated by editing that favours rapid cuts over logic — the film’s pulse races, but its heart falters. The result is an experience that dazzles visually but feels narratively hollow, more like a hypnotic music video than a fully realized character study. Indeed, the ending drops the ball most of all. The nightmarish satire culminates in a bloodbath which, while visually powerful, feels like something more twisted and subtle would have served Cam’s character arc better.

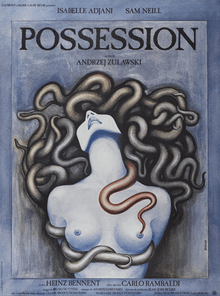

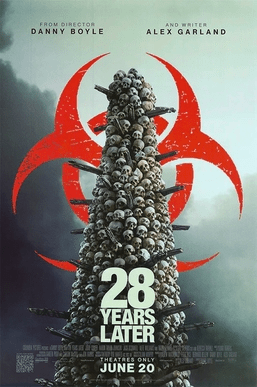

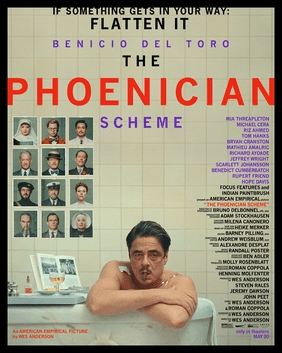

Overall, there’s no denying Him (2025) and its impact as a cinematic spectacle, with Wayans and Withers delivering standout performances. Its imagery lingers — bodies breaking under fluorescent light, cheers warping into screams — as does its commentary on the performative nature of modern masculinity, crazy fan worship, monetization of athletes and sporting sacrifice. If only the script matched its visuals, Him (2025), might have stood shoulder to shoulder with the psychological thrillers it so clearly reveres.