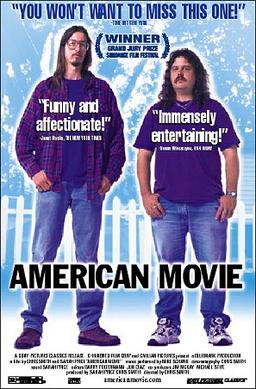

Cult Film Review: American Movie (1999)

Directed by Chris Smith

Produced by Sarah Price & Chris Smith

Main “Cast”: Mark Borchardt and Mike Schank

Cinematography by Chris Smith

Edited by Barry Poltermann & Jun Diaz

Music by Mike Schank

*** MAY CONTAIN SPOILERS ***

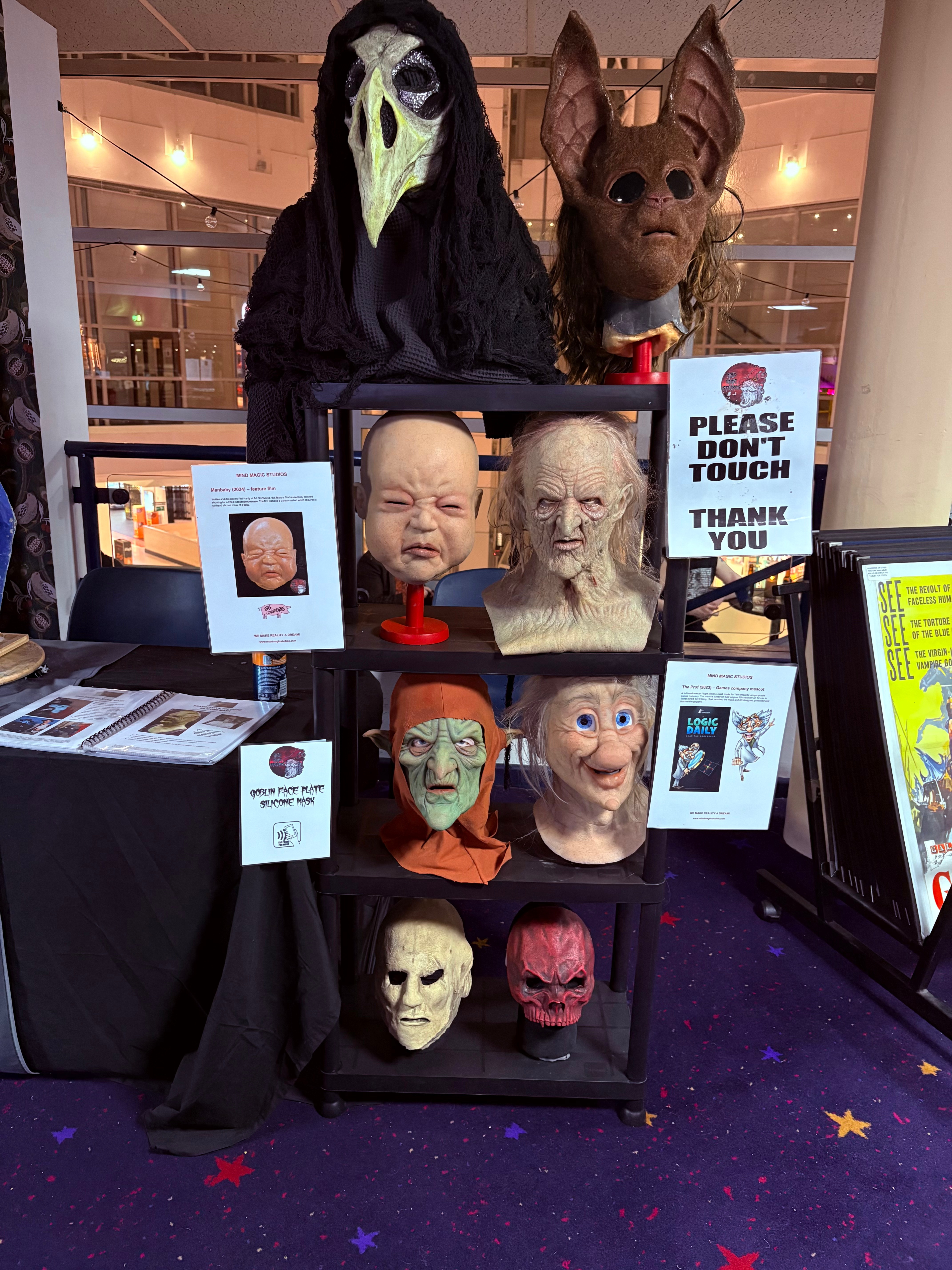

Given I am a low-budget filmmaker myself I am amazed I had never seen, American Movie (1999) before. Thankfully The Nickel Cinema in London screened it at the weekend and I really enjoyed it. Filmed between 1995 and 1997, this cult classic documentary American Movie (1999) chronicles Borchardt’s heroic, chaotic, and deeply Midwestern quest to finish his indie horror short Coven (pronounced ‘COH-ven’, and yes, he will correct you). The short is meant to raise money for his real passion project, a feature called Northwestern. But first? He has to survive reality. And reality is brutal.

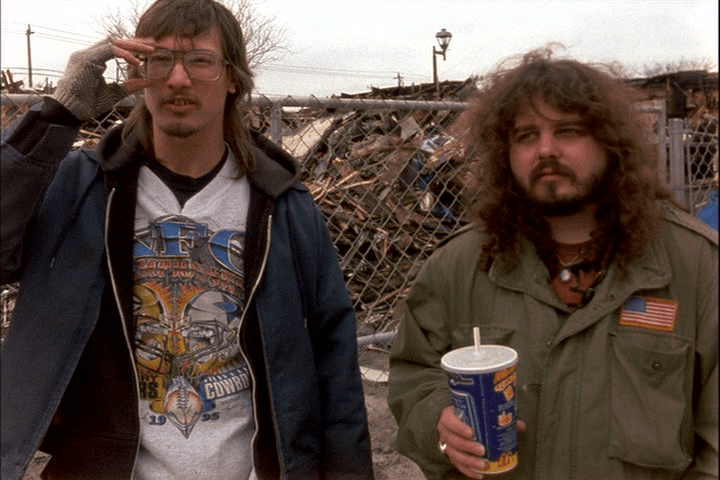

Mark has not just zero money; zero organization; a rotating cast of confused friends and relatives as crew; functioning alcoholism; mounting debts, but also has the gift of the gab and a never ending passion for filmmaking. What unfolds is less “behind-the-scenes documentary” and more Shakespearean comedy AND tragedy staged in Milwaukee houses, static caravans, cars, junkyards and local woods.

Borchardt is equal parts Ed Wood and tortured auteur — passionately explaining his artistic vision one minute, begging his elderly uncle for production money and picking up his editing assistant from prison the next. His crew ranges from loyal-but-clueless to openly skeptical, yet somehow the production lurches forward. Barely.

The documentary crew shot over 90 hours of 16mm footage, capturing every awkward take, every blown line, and every moment of Mark’s delusional optimism. We watch as Coven repeatedly derails thanks to bad planning, worse luck, and the universal law that says: if something can go wrong on an indie film set, it absolutely will. But here’s the twist — it’s weirdly inspiring. Because underneath the chaos is something pure: a guy who just refuses to stop making movies. No money. No resources. No safety net. Just pure passion and obsession.

What’s most hilarious is the double act comedy exchanges between Mark and his best friend and Mike Schank. Mike, a very capable musician, has a permanent grin and the look of an acid-trip casualty, yet almost-perfect comedy timing. He clearly loves Mark’s passion and helps as best he can. I was sad to read Mike had passed away in 2022 from cancer.

If you stumbled into American Movie (1999) blind, you’d swear it was a proto-sitcom about delusional dreamers armed with a battered 16mm camera, a camcorder and misplaced confidence — a spiritual ancestor to Trailer Park Boys and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. It plays like a painfully funny hangout comedy about a self-proclaimed auteur and his band of well-meaning screw-ups trying — and repeatedly failing — to make something “serious.” The arguments are petty, the ambition is sky-high, and the incompetence is operatic. You laugh, you cringe, and somewhere along the way you realize this isn’t scripted chaos — it’s just raw, unfiltered obsession captured on camera.